On this page, the Historical Society will be presenting a series of presentations and essays written by Roger Glass.

Roger S. Glass is the great grandson of the late Clarence Jackson and the late Addie Jackson, both longtime Tarrytown residents; the grandson of the late Virginia Jackson Nelson and the late Henry Nelson, both lifelong Tarrytown residents; and the son of Alba Nelson Glass, who was born and raised in Tarrytown. Roger was born in Tarrytown in 1952 and currently resides in Washington, DC. You can visit his family history blog at www.roger-glass.com.

2023 Essay

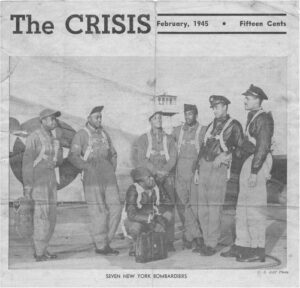

A son of Tarrytown serves his country as a member of the prestigious Tuskegee Airmen

In the immediate aftermath of Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, able-bodied American men from ages 18 to 41 were required to make themselves available for military service. My uncle, James Conway, was among the dozens of Tarrytowners who flocked to the local draft board office to register for potential military service during World War II. However, James’s younger brother, C. Channing “Bubby” Conway, had already joined the Army. A 1941 graduate of Washington Irving High School, Uncle Bubby was stationed at McClellan Air Force Base in California.

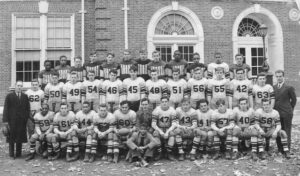

Clarence “Bubby” Conway (seated on ground center) with members of the Washington Irving High School football team (c. 1941).

Clarence “Bubby” Conway (seated on ground center) with members of the Washington Irving High School football team (c. 1941).

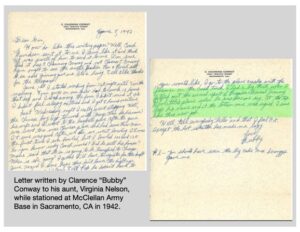

In a letter dated June 5, 1942, Uncle Bubby told his aunt (and my grandmother), Virginia Nelson, about his brush with military fame when he was responsible for recording the arrival of the plane of famed WW II air commander Jimmy Doolittle, the first Air Force general to wear four stars. “I had a big thrill when I filled out the arrival report of Brigadier-General Jimmy Doolittle’s plane when he was here one day. At the top was his name at the bottom mine was signed,” Uncle Bubby wrote.

After spending time at McClellan, Uncle Bubby was selected to become a member of Tuskegee Airmen, a prestigious group of African Americans who were trained as pilots and mechanics in a program established by the U. S. Army Air Corps (predecessor to the modern-day U.S. Air Force) in conjunction with Alabama’s Tuskegee University.

After spending time at McClellan, Uncle Bubby was selected to become a member of Tuskegee Airmen, a prestigious group of African Americans who were trained as pilots and mechanics in a program established by the U. S. Army Air Corps (predecessor to the modern-day U.S. Air Force) in conjunction with Alabama’s Tuskegee University.

Prior to the creation of the Tuskegee program Black people were not permitted to participate in the war as airmen because there was a belief that they could not learn to fly sophisticated aircraft. “What happened is that Congress finally puts pressure on the War Department to allow African Americans to train to be pilots, and the War Department figures they don’t have the skills, the abilities or bravery to be airmen. They think, ‘What we’ll do is send them to Alabama and attempt to train them, but we expect that they will fail,’” explained Spencer Crew, the former interim director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Prior to the creation of the Tuskegee program Black people were not permitted to participate in the war as airmen because there was a belief that they could not learn to fly sophisticated aircraft. “What happened is that Congress finally puts pressure on the War Department to allow African Americans to train to be pilots, and the War Department figures they don’t have the skills, the abilities or bravery to be airmen. They think, ‘What we’ll do is send them to Alabama and attempt to train them, but we expect that they will fail,’” explained Spencer Crew, the former interim director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“But instead, what happened is that these really, brilliant men go to Tuskegee, dedicate themselves to learn how to fly and become a very important part of the Air Force. They were highly trained when they got to Tuskegee in the first place. Some had been trained in the military, many had been engineers, and they just brought a very high skill level with them to this work.”

The Tuskegee Airmen would make a pioneering contribution to the war and the subsequent drive to end racial segregation in the American armed forces. Altogether, 992 pilots graduated from the Tuskegee Air Field courses, and they flew 1,578 missions and 15,533 sorties, destroyed 261 enemy aircraft, and won more than 850 medals.

In the years following the war, Uncle Bubby rarely talked about WW II or his military service. When he did, he would recall the racism and segregation faced by him and other Black people who fought in WW II. However, Uncle Bubby remained proud to have served his country and to have helped integrate the American armed forces and breakdown stereotypes regarding the abilities of Black men and women.

In the years following the war, Uncle Bubby rarely talked about WW II or his military service. When he did, he would recall the racism and segregation faced by him and other Black people who fought in WW II. However, Uncle Bubby remained proud to have served his country and to have helped integrate the American armed forces and breakdown stereotypes regarding the abilities of Black men and women.

2022 Essay

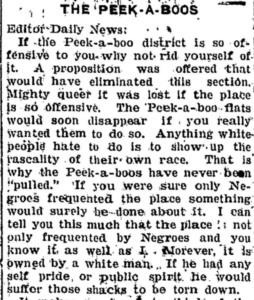

Black soldiers’ presence heightened concerns about Tarrytown’s controversial “peek-a-boos”

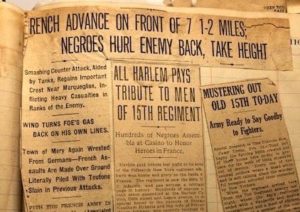

One of the more remarkable stories to come out of World War I was the heroism of a regiment of Black fighters. With segregation still very much a way of life in the United States, the 369th Infantry Regiment, known initially as the 15th National Guard New York, was the first Black infantry allowed to fight in World War I.

Prior to shipping out to France in December 1917, the regiment trained at an army camp near Peekskill, NY. While there, members of the regiment would come to Tarrytown to visit the popular—and increasingly controversial—”peek-a-boos” (peek-a-boos are now what’s known as strip clubs).

Tarrytown residents and some of the town’s elected leaders regularly complained about the peek-a-boo—and were actively trying to get them permanently shutdown.

Photograph of Peek-a-boo flats (ca.1911) from the Historical Society Collection.

Photograph of Peek-a-boo flats (ca.1911) from the Historical Society Collection.

“The peek-a-boos give the police more trouble than any other section,” an editorial in the Tarrytown Daily News said. “They operate in violation of the law. They should be closed and we hope village authorities will take some action to have them removed.”

The presence of the Black soldiers only served to heighten the criticism of the peek-a-boos, with a number of Tarrytowners charging that the visitors from the Peekskill training camp were loud and rowdy.

Those claims prompted a letter to the editor of the Tarrytown Daily News from Beatrice Jackson. A staunch advocate for the village’s Black community as well as members of her race, Jackson, in the July 17, 1917 letter, reminded residents of Tarrytown that they were given an opportunity to support a measure that would have gotten rid of the peek-a-boos but took no action.

“A was offered that would have eliminated this section. The peek-a-boo flats would soon disappear if you really wanted them to,” she wrote.

“A was offered that would have eliminated this section. The peek-a-boo flats would soon disappear if you really wanted them to,” she wrote.

The fact that white men regularly frequented the peek-a-boos was the primary reason they were not shutdown, Jackson asserted. “If you were sure only Negroes frequented the place something would surely be done about it.”

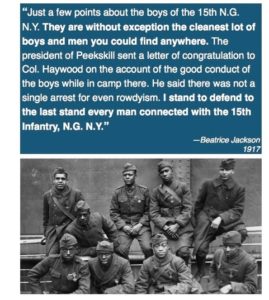

In her letter, Jackson defended the character of the men of the 369th Infantry Regiment, who would later earn the nickname the Harlem Hellfighters for the toughness and fighting skills they displayed during the war.

“Just a few points about the boys of the 15th N.G. N.Y. They are without exception the cleanest lot of boys and men you find anywhere. The president of Peekskill sent a letter of congratulation to Col. Haywood on the account of the good conduct of the boys while in camp there. He said there was not a single arrest for even rowdyism. I stand to defend to the last stand every man connected with the 15th Infantry, N.G. N.Y,” Jackson wrote.

At the end of the war, the 369th returned to New York City, and on February 17, 1919, paraded through the city. Thousands of mostly Black New Yorkers lined the streets to see the 369th Regiment. The parade became a marker of African American service to the nation, a frequent point of reference for those campaigning for civil rights.

Image of one of the pages of Beatrice Jackson’s scrapbook. Courtesy of Roger Glass.

Image of one of the pages of Beatrice Jackson’s scrapbook. Courtesy of Roger Glass.

2020 Presentation

Click on image at left to read.

Click on image at left to read.

2019 ESSAY NUMBER 2

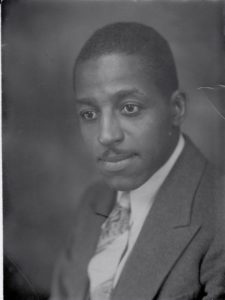

CLARENCE C. JACKSON JR.

Tarrytown’s Legendary High School Athlete

In the early 1920’s, one name stood out among the outstanding athletes at Washington Irving High School—Clarence Channing Jackson, Jr. A legendary football player and track and field star, Jackson’s exploits were regularly touted in the Tarrytown Daily News.

In the early 1920’s, one name stood out among the outstanding athletes at Washington Irving High School—Clarence Channing Jackson, Jr. A legendary football player and track and field star, Jackson’s exploits were regularly touted in the Tarrytown Daily News.

“Chan Jackson Makes 65-Yard Run for Touchdown,” a headline from the Nov. 24, 1921 issue of the paper shouted.

“It was a common occurrence for young Jackson to make  exceptional long runs and win (football) games within seconds of the final period,” a 1961 article in the same newspaper says. His “terrific burst of speed and his ability to twist, turn, weave and dodge were executed quicker than the bat of an eyelid.”

exceptional long runs and win (football) games within seconds of the final period,” a 1961 article in the same newspaper says. His “terrific burst of speed and his ability to twist, turn, weave and dodge were executed quicker than the bat of an eyelid.”

Another Tarrytown Daily News article, penned by Wally Buxton in May 1960, recalled Jackson’s track and field feats. “On Memorial Day 1922, a track meet was held under the auspices of Washington Irving High School. Six schools competed in the annual meet.” Buxton further wrote “the star of the day was Clarence ‘Chan’ Jackson, certainly a wonder athlete for a boy. His running was tops and his winning of the running jump was thrilling. In the pole vault he established a new record and ran away from the field in the relay race.”

Another Tarrytown Daily News article, penned by Wally Buxton in May 1960, recalled Jackson’s track and field feats. “On Memorial Day 1922, a track meet was held under the auspices of Washington Irving High School. Six schools competed in the annual meet.” Buxton further wrote “the star of the day was Clarence ‘Chan’ Jackson, certainly a wonder athlete for a boy. His running was tops and his winning of the running jump was thrilling. In the pole vault he established a new record and ran away from the field in the relay race.”

In that same article, Buxton, who grew up with Jackson, reminisced about their childhood together. “I have known ‘Chan’ since 1906. He lived at 62 John Street and he had a wonderful home environment…..

I remember best the days we kicked goals in Cobb’s Lot when Chan Jackson, Johnny Gross, Buck Weaver, Irving Williams, and George Lemon would play against Bill Gross, George Cole, Joe Quinn, Lester Delancy, Red Fisher and Rollie Willams,” Buxton wrote.

Upon his graduation from Washington Irving in 1922, a newspaper editorial said this about Clarence Channing Jackson, Jr.: “We are frank to admit that it will be some years before another Jackson is discovered. He is a wonder-athlete.”

Upon his graduation from Washington Irving in 1922, a newspaper editorial said this about Clarence Channing Jackson, Jr.: “We are frank to admit that it will be some years before another Jackson is discovered. He is a wonder-athlete.”

Jackson went on to star in track at Springfield College in Massachusetts, where he earned a degree in physical education, and would later coach the first women’s track team to compete internationally.

An Advocate for Baltimore’s Black Youth

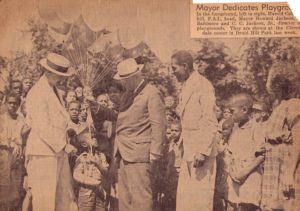

Jackson may have saved his best and most important victories for the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s. In 1929, the Tarrytown native took a position with the Baltimore Department of Recreation. He was given responsibility for the recreational activities and sports programs for the city’s black youth.

Jackson “organized much of the first amateur sports activities for black Baltimoreans,” a 1972 Baltimore newspaper article said. Jackson told the paper that he “used every trick in the trade, every trick that I could command to gain facilities and opportunities” for black youth.

Ironically, though not surprisingly, a half-century earlier Jackson’s mother, Addie Jackson, had argued for more recreational opportunities for black youth in Tarrytown. Addressing an advisory group set up in the early 1900s to make recommendations for improving the village, Momma Addie said this: ‘There is no recreation for colored boys and girls in Tarrytown. The civic league does wonderful work, but outside of that there is no means of recreation provided for us.”

Clarence Jackson would become the first black supervisor in the city of Baltimore’s recreation department and, in 1977, the city honored him with the opening of the “C.C. Jackson Recreation Center” in north Baltimore. “I was pleased to read of his (Jackson’s) rise to honor in the Baltimore Press,” his old friend Buxton wrote in the 1960 article. “It was a long overdue tribute to a clean-cut American boy.”

Clarence Jackson would become the first black supervisor in the city of Baltimore’s recreation department and, in 1977, the city honored him with the opening of the “C.C. Jackson Recreation Center” in north Baltimore. “I was pleased to read of his (Jackson’s) rise to honor in the Baltimore Press,” his old friend Buxton wrote in the 1960 article. “It was a long overdue tribute to a clean-cut American boy.”

2019 ESSAY NUMBER 1

CELEBRATING TARRYTOWN’S BLACK HISTORY

Family Starts Red Cross Chapter to Aid

Black Soldiers Fighting in World War I

When World War I broke out in 1914, Americans were encouraged to knit items to be sent to the troops. Tarrytown’s Addie Jackson and her daughters Beatrice, Virginia and Marie pitched in by knitting socks, scarves and gloves for the servicemen. “On Sundays in those days everyone would make a pair of socks and there’d be at least four pairs of socks by the end of the day and gloves and scarves by the end of the week,” Marie Jackson said in a 1981 article published in the Tarrytown Daily News.

However, when Addie Jackson learned that these clothing items were not being sent to black soldiers, she and her daughters started a Red Cross chapter in their Tarrytown home, and began knitting and sending scarves, gloves and socks to the black troops.

“We started the Red Cross in Tarrytown because it (the Red Cross) was segregated in those days,” Virginia Jackson told the Tarrytown newspaper. “They wouldn’t take blacks and there were blacks fighting in the 369th Regiment. So mother started the Red Cross in our home.”

That was the start of almost 70 years of Red Cross involvement on the part of the Jackson family. Over the next several decades, Marie (Jackson) Plater and Virginia (Jackson) Nelson would become tireless and distinguished Red Cross volunteers.

In the 1970s, Marie founded a “call program” for the Tarrytown chapter of the Red Cross that would become a model for Westchester County. She directed volunteers from branches across the county who once a week would call to check up on housebound or ill senior citizens.

In the 1970s, Marie founded a “call program” for the Tarrytown chapter of the Red Cross that would become a model for Westchester County. She directed volunteers from branches across the county who once a week would call to check up on housebound or ill senior citizens.

Marie is also credited  with originating Early Alert, a cooperative effort between the post office and the Red Cross. A March 1981 article in the Tarrytown Daily News described the Early Alert program this way: “If an older person’s mail remains untouched for three days, the letter carrier contacts Red Cross volunteers who investigate to make sure the person is safe.”

with originating Early Alert, a cooperative effort between the post office and the Red Cross. A March 1981 article in the Tarrytown Daily News described the Early Alert program this way: “If an older person’s mail remains untouched for three days, the letter carrier contacts Red Cross volunteers who investigate to make sure the person is safe.”

In 1968, Virginia Nelson was recognized for 50 years of service to the Red Cross. At the time, she was the Tarrytown chapter’s production chairman. Not surprisingly, the work she was doing in that capacity was consistent with the family tradition. “Mrs. Nelson has earned a reputation at Chapter headquarters for invariably being able to fill requests for sweaters, afghans, gift bags or whatever other knitting and sewing is needed,” a newspaper article said in a report on Virginia’s recognition for 50 years of service.

2018 ESSAY NUMBER 4

114 year old Tarrytown “Negress” is celebrated as nation’s “oldest voter”

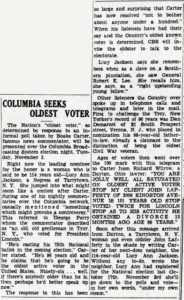

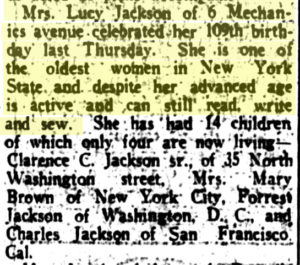

Born into slavery in Nelson County, VA in 1821, Lucy Ann Jackson became a Tarrytown celebrity, of sorts, more than a century later when she was celebrated as possibly the oldest person in America.

Jackson, who was a slave from birth until the end of the Civil War, had moved to Tarrytown in the late 1800s to join her adult children, most of who had previously migrated to New York State.

Jackson, who was a slave from birth until the end of the Civil War, had moved to Tarrytown in the late 1800s to join her adult children, most of who had previously migrated to New York State.

In 1935, the Columbia Broadcasting System sought to identify the “oldest voter” in America. One of Jackson’s Tarrytown neighbors told them about her. “Right now the leading nominee for the honor is a woman said to be 114 years old—Lucy Ann Jackson, a Negress of Tarrytown,” a newspaper article said. Much fanfare greeted Mrs. Jackson when she walked from her house to register to vote at her local polling place.

A Tarrytown Daily News reporter assigned to interview the 114 year old Jackson had this to say: “The assignment to interview a woman more than a century old conjures visions in the mind of a frail figure reclining in bed looking back through the corridors of time with little inclination or ability to talk about life and its milestones….But walking in the door of Mr. Carrie Richardson’s home at 82 Depeyster Street this morning, no bed or invalid chair was pointed out. There was Mrs. Jackson, at the age of 114, busily mending a pair of trousers with quick accurate strokes of the needle.”

An earlier newspaper article written about  Jackson when she turned 111 noted “she has never suffered a serious illness and has never been ill enough to call a doctor….She is one of those people blessed with a cheerful disposition and she seems to have a peculiar way of overcoming worries. ‘Don’t worry, work hard and take care of your health’ are the simple, well-known bits of advice that have enabled Mrs. Jackson to laugh in the face of Father Time.”

Jackson when she turned 111 noted “she has never suffered a serious illness and has never been ill enough to call a doctor….She is one of those people blessed with a cheerful disposition and she seems to have a peculiar way of overcoming worries. ‘Don’t worry, work hard and take care of your health’ are the simple, well-known bits of advice that have enabled Mrs. Jackson to laugh in the face of Father Time.”

2018 ESSAY NUMBER 3

Black Community Rallies Behind “the Party of Lincoln”

It should come as no surprise that during the early 1900s most black Americans held an allegiance to what was widely known as “the party of Lincoln”—the Republican Party. This was true in Tarrytown and North Tarrytown where the Colored Republican Club of the Tarrytowns was a fixture in local and Westchester County politics. The club regularly hosted forums and rallies where local black residents heard from candidates for elected office—and pledged their support to the Republican candidates.

Shiloh Baptist Church pastor, Reverend C.L. Franklin, was one of the villages’ most influential black leaders at the time. The Tarrytown Daily News reported that he said the following to a meeting held by the Colored Republican Club of the Tarrytowns in the late 1920s in support of Republican candidates for local and county offices.

Shiloh Baptist Church pastor, Reverend C.L. Franklin, was one of the villages’ most influential black leaders at the time. The Tarrytown Daily News reported that he said the following to a meeting held by the Colored Republican Club of the Tarrytowns in the late 1920s in support of Republican candidates for local and county offices.

“Stick by your party. Don’t jump from one side to the other. It won’t do you any good and you won’t be satisfied…If we don’t like the candidates who are offered to us it is not for us to jump to the other side but to bide our time and at the next opportunity insist on men we do like.”

“I have been a resident of the Tarrytowns for five years and I have made a study of this community. We’re all a part of it and we know what the Republican organization has done for us. Let every clear thinking individual stand at the polls next Tuesday and support the Republican ticket,” Rev. Franklin added.

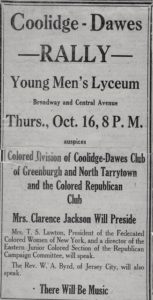

The Tarrytowns’ “colored” community was also politically active during national elections. In October 1924, the Colored Republican Club of the Tarrytowns joined with the Westchester County Negro League to sponsor a rally on behalf of Republican presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge, who would be elected president of the United States the following month.

The Tarrytowns’ “colored” community was also politically active during national elections. In October 1924, the Colored Republican Club of the Tarrytowns joined with the Westchester County Negro League to sponsor a rally on behalf of Republican presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge, who would be elected president of the United States the following month.

Four years later, the towns’ black community, led by the Colored Women’s Hoover-Curtiss Campaign Committee, came together in support of the presidential candidacy of Herbert Hoover, who was elected president in November 1928.

2018 ESSAY NUMBER 2

Growing Cotton in a Tarrytown Backyard

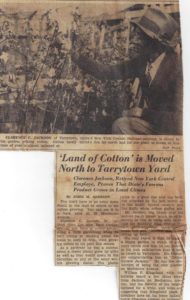

Exposed to cotton as a child growing up in Virginia in the 1870s, Clarence Jackson Sr. was certain he could grow “King Cotton” in the north. So when friends and family told the longtime Tarrytown resident that he couldn’t grow cotton in his Mechanics Avenue backyard, he set out to prove them wrong. And he did.

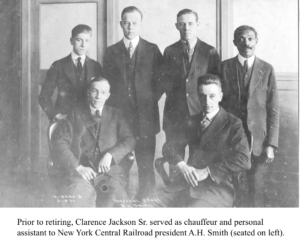

Clarence Jackson Sr. arrived in Tarrytown in the mid-1880s. In 1892, at the age of 27, he landed a job at Grand Central Station as a messenger with New York Central Railroad. He would eventually rise to the position of chauffeur and personal assistant for several of the railroad’s presidents, including Alfred H. Smith, who presided over New York Central Railroad during its heyday (1914 -1924).

When Jackson retired in 1935 an article published in the Tarrytown Daily News the day before he retired stated: “Mr. Jackson met many dignitaries from all parts of the world” during his 42 years as an employee of New York Central Railroad.

When Jackson retired in 1935 an article published in the Tarrytown Daily News the day before he retired stated: “Mr. Jackson met many dignitaries from all parts of the world” during his 42 years as an employee of New York Central Railroad.

“As a gardener he [Jackson] was a success, about a dozen plants grew up quite as well as they would down in the Carolinas or any other cotton growing states,” a December 1941 article in the Tarrytown Daily News said.

“Mr. Jackson was happy over his success for it meant much satisfaction to him being able to refute the doubting folks who at the start of the season shook their heads and said, ‘Jackson can’t grow cotton up here’.” The caption that ran with a photo of Jackson and his cotton reported: “Cotton rarely thrives this far north and for the plant to bloom at this time of year is almost unheard of.”

Some years later another Tarrytown Daily News article also mentioned Jackson’s cotton growing skills. “Mr. Jackson only tried growing cotton as a fad, but as he kept cultivating it, the cotton kept growing and blossomed into as fine a plantation as one would find in the heart of the Carolinas or Tennessee.”

2018 ESSAY NUMBER 1

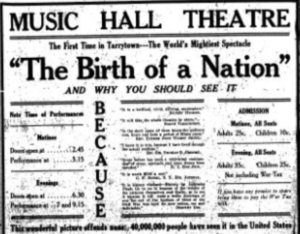

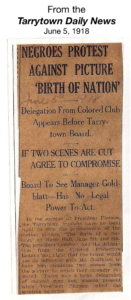

Town’s “Colored Community” rises up to protest showing of “The Birth of a Nation”

When the movie “The Birth of a Nation” was released in 1915 it was immediately met with controversy and protests. Set in the South during and after the Civil War, the movie depicted black men as lawless and dangerous—and portrayed the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force.

Black Americans and others were outraged by this biased view of reality. That outrage found its way to Tarrytown in 1918 when plans were announced to show “The Birth of a Nation” at Music Hall.

Tarrytown’s Colored Protective League organized a meeting at Shiloh Baptist Church to protest the plan to show the movie. “This immoral play written by Rev. Thomas Dixon causes race hatred, and in many places in the South where the picture has been shown lynchings and race troubles have resulted afterwards which were directly traceable to the evil effects of this picture,” an article in Tarrytown Daily News announcing the meeting said.

In the aftermath of the meeting at Shiloh, “a large delegation of colored men and women” attended a meeting of the Tarrytown Board of Trustees to protest the showing of the movie, the newspaper reports.

According to the Tarrytown Daily News, Colored Protective League spokesperson William Kingsland told the town’s trustees that the movie “breeds antagonism against the colored race and wherever it has been shown there has been trouble.”

Another spokesperson, Daniel Teagle, said the delegation of colored men and women were present “to register sincere and unreserved protest against the presentation of scenes (in the movie) which have no laudable purpose.” He went on to say that the picture “was not elevating, but that it sought to destroy the moral fabric which the Negroes by their forbearance and patience and acquiescence to self-government had built up.”

Another spokesperson, Daniel Teagle, said the delegation of colored men and women were present “to register sincere and unreserved protest against the presentation of scenes (in the movie) which have no laudable purpose.” He went on to say that the picture “was not elevating, but that it sought to destroy the moral fabric which the Negroes by their forbearance and patience and acquiescence to self-government had built up.”

Beatrice Jackson-Conway, who held the distinction of being the first black girl to graduate from Washington Irving High School, spoke “in defence of the Negro,” the paper says. She warned town leaders that showing the movie “would start trouble” and that “she did not see how cutting out two scenes from the picture was going to help any.”

Beatrice Jackson-Conway, who held the distinction of being the first black girl to graduate from Washington Irving High School, spoke “in defence of the Negro,” the paper says. She warned town leaders that showing the movie “would start trouble” and that “she did not see how cutting out two scenes from the picture was going to help any.”

The meeting ended with Board of Trustee President Frank Pierson promising to bring the colored community’s concerns about the movie to the attention of Music Hall owner Robert Goldblatt.

Roger S. Glass is the great grandson of the late Clarence Jackson and the late Addie Jackson, both longtime Tarrytown residents; the grandson of the late Virginia Jackson Nelson and the late Henry Nelson, both lifelong Tarrytown residents; and the son of Alba Nelson Glass, who was born and raised in Tarrytown. Roger was born in Tarrytown in 1952 and currently resides in Washington, DC. You can visit his family history blog at www.roger-glass.com.